Every weekday evening, our editors guide you through the biggest stories of the day, help you discover new ideas, and surprise you with moments of delight. Subscribe to get this delivered to your inbox.

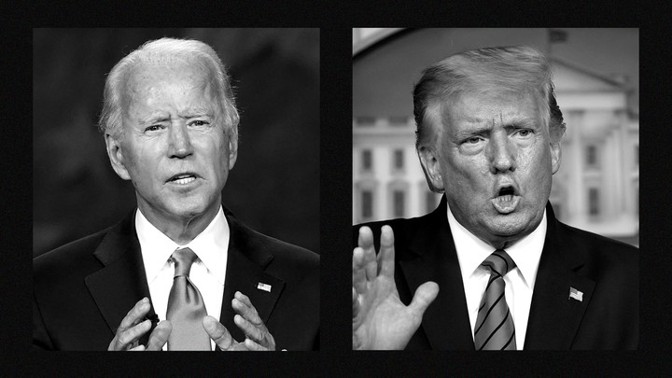

President Donald Trump held up a mirror to the American foreign-policy establishment, two of our writers argue, forcing it to reckon with a broken status quo.

“Trump may have no idea that he is revealing any of this; he may not even agree with the things he is revealing,” Tom McTague and Peter Nicholas write. “Yet he is revealing them nonetheless.”

Tom and Peter, who are based in London and Washington, D.C., respectively, conducted several dozen interviews with experts in the United States and in Europe, as well as current and former administration officials. Below are three of their takeaways from the past four years of Trumpism:

1. Trump revealed a new world order.

After decades of international adventures that have left the U.S. overstretched, overwhelmed, and overburdened, it was Trump who blurted out the uncomfortable truth: American foreign policy was failing, and had been for decades.

2. His foreign policy remains driven by naïveté …

Time and again, we were struck by the assessment, related by multiple sources in separate meetings, that Trump’s most important characteristic when it came to foreign policy was not what his critics charge—his amorality or vindictiveness, his lack of success or diplomatic vandalism. They said … [it] was his naïveté.

3. … and, practically speaking, empty.

Trump, even as he calls out the American-built world order for its failures, has no coherent plan to replace it, no system that would work better. He isn’t trying to reorder the world; he’s just pointing at the order and calling it naked. Or as [Fiona Hill, Trump’s former senior director on European and Russian affairs at the National Security Council] put it: “He’s a chaos agent.”

Further reading: These world leaders want Trump to win the election, Yasmeen Serhan reports.

14 days remain until the 2020 presidential election. This is today’s essential read:

The far-right misinformation ecosystem is preparing for the possibility that Trump might lose, Renée DiResta reports.

“Its goal is simple—to preemptively delegitimize any outcome but a clear victory by the incumbent.”

Want to better understand the ongoing coronavirus outbreak? Here are four key stories from our team:

Stuck on what to stream? Let us help:

’Tis the season for a fright. Our critic David Sims selected 25 of the best horror films, ranked by scariness.

Today’s break from the news:

“Our boyfriends, our significant others, and our husbands are supposed to be No. 1. Our worlds are backward.” Rhaina Cohen writes about people who consider a friend to be their life partner.

Did someone forward you this newsletter? Sign up here. Need help? Contact Customer Care.

from The Atlantic https://ift.tt/2IMkVGR

Today, The Atlantic launched Planet, a new section devoted to climate change, along with The Weekly Planet, a new newsletter written by Robinson Meyer. He also writes today’s edition of the Daily, explaining why the climate story is so exciting right now.

I’ve been covering climate change at The Atlantic for five years. There’s still one question I get more than any other: Are you hopeful? At this point, honestly, I find the question to be a little beside the point: If you don’t want the planet to warm, you should work to reduce carbon pollution regardless of whether you’re hopeful about the overall outcome.

Many things in the world aren’t going well, to put it mildly. But the fight against climate change got some excellent news this week.

The International Energy Agency announced, in its enormously influential annual report, that solar energy is now the “cheapest electricity in history.” At the same time, it substantially downgraded its forecast for coal, saying that the fuel source will soon enter a prolonged and irreversible decline. That means global carbon pollution could peak in the next several years—though, without further policy, it will not decline as rapidly as needed to avoid catastrophic global warming.

But in the past few years, the outlook has brightened—even as the disastrous consequences of climatic upheaval have gotten worse. For years, the goal of climate policy was to make renewable energy cost-competitive with fossil fuels. Now that’s a reality.

In the next few weeks and months, we’ll learn what kind of policy such breakthroughs will enable—and what new ideas and tools we still need along the way. If that sounds interesting—or even if you wish you spent more time every week keeping up with climate change—please subscribe to The Weekly Planet.

More from our new Planet section:

-

Vann R. Newkirk II on Earth’s new gilded era

-

Sabrina Imbler on why you should kill your gas stove

-

Lawrence Weschler on the climate fight’s Scylla and Charybdis

One question, answered: Are gas stoves bad for you?

Our science editor Sarah Laskow explains:

About a third of American households rely on natural gas to cook, and although starting a small gas fire in the kitchen might seem mundane, it’s surprisingly dangerous to human health. The science journalist Sabrina Imbler looked into this for us, and concluded that anyone who can afford to avoid cooking with gas probably should.

The main problem is that gas stoves spew pollution inside the house, at levels that would be illegal outdoors. One of these chemicals, nitrogen dioxide—which is also found in car exhaust—can cause people with respiratory issues to cough and wheeze, and people without respiratory issues to develop them.

Gas stoves also require buildings to have gas lines, which require extensive gas infrastructure. That setup helps keep residential areas from switching over entirely to renewable energy.

Electric stoves do use more energy, but they do not spew noxious chemicals into your kitchen. And a number of chefs promised that an induction stove can do almost anything a gas stove can. (They were, however, divided on the subject of stir-fry.)

19 days remain until the 2020 presidential election. Here’s today’s essential read:

Barack Obama is “an arena politician, strongest in front of a crowd cheering for him.” That’s not an option this year, so he’ll campaign for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris in other ways, Edward-Isaac Dovere reports.

Today’s break from the news:

Speaking of our extraordinary planet: Take a moment to browse this inspiring collection of wildlife photography.

Did someone forward you this newsletter? Sign up here. Need help? Contact Customer Care

from The Atlantic https://ift.tt/3dDrcAc

On the White House grounds this morning, senior West Wing aides walked around without masks. They spoke with the press without masks. They huddled privately with one another and didn’t wear masks.

When I visited the White House in August, no one checked to see if I was running a fever or suppressing a hacking cough as I passed through the security booth. The ritual was the same today: I showed up hours after we’d learned that President Donald Trump had tested positive for the coronavirus, yet no one asked about my health. Instead, I was simply searched for weapons and allowed in.

I’ve written twice in recent months about the dangerous conditions around the president—about lax testing of journalists flying with him on Air Force One, about troubling working arrangements inside the executive mansion itself. Trump’s illness seems an outgrowth of the administration’s flagrant disregard for public-health precautions. And yet, there’s no sign of a real course correction: The practices today seemed every bit as lax. When Trump walked deliberately toward Marine One tonight, in a dark suit and matching mask, he waved to reporters who all day had been trying to find out information about his condition.

But he left a White House that, even though he’s been stricken with a potentially fatal disease, seemed no safer than at any other point in the pandemic. Officials don’t appear to have learned much from the nightmare.

As far as I could tell, the White House’s lone concession to the catastrophe unfolding before our eyes was that a few junior aides working in the suite of offices accessible to the press corps sat at their desks in masks. During my August trip, none of the aides breathing the same air in this cramped warren of offices had seen fit to wear them.

[David A. Graham: Trump’s denial has now produced what he feared]

On this day, of all days, a mask would have seemed indispensable. But a senior White House official told the Associated Press this afternoon that masks amount to a “personal choice.” Larry Kudlow, the president’s top economic adviser, was effectively goaded into wearing one during an impromptu press conference today. Kudlow said he wanted to make sure the press could hear him while keeping his distance, and so he hadn’t worn a mask. When a reporter suggested that he set an example for the nation, he put one on.

When White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows spoke with reporters on the north driveway this morning, he didn’t wear one at all. In a seven-minute appearance, the barefaced Meadows efficiently demonstrated so much of what’s gone wrong with the White House’s handling of the pandemic. He opened not by talking about the shattering revelation that the 45th president of the United States is infected, but by touting monthly job numbers that might prove helpful to Trump’s reelection. Meadows spoke vaguely about “protocols in place” to keep everyone healthy. When CNN’s Jim Acosta asked him why he wasn’t wearing a mask, Meadows trotted out the same tired defense that the White House deployed from the start: He gets tested regularly.

But of course, so does Trump. And yet Trump was inside, sick. “In true fashion,” Meadows said, his boss was probably watching TV and “critiquing the way that I’m answering these questions.”

Inside the building, the atmosphere seemed tense. A former administration official, speaking on condition of anonymity in order to be frank, told me he’s worried that he’s been exposed and plans to get tested. More people at the White House are getting infected, as Meadows predicted this morning they would. Yesterday came news that Trump’s senior adviser Hope Hicks was ill. Today it was a press aide who tested positive, along with a group of journalists.

Unless and until the White House starts taking this pandemic much more seriously, anyone visiting the grounds is at risk. The president has been for months. After my visit in August, I wrote that if I’d torn off my mask and had a coughing fit inside the White House, it didn’t seem like anyone would’ve especially cared. That felt true today too. But by then, it wouldn’t have mattered. Whatever illness I’d brought into the building would’ve already been in the air.

from The Atlantic https://ift.tt/2GxDY6y

Every weekday evening, our editors guide you through the biggest stories of the day, help you discover new ideas, and surprise you with moments of delight. Subscribe to get this delivered to your inbox.

The early-morning revelation that the president tested positive for the coronavirus set off a cascade of questions. When did Trump catch the coronavirus? What does his diagnosis mean? And who else in the White House might be sick?

The answers aren’t clear-cut. Below, our reporters offer their best guidance based on the limited information available and their conversations with experts. We hope it can help you make sense of this moment.

What are the possible outcomes of Trump’s diagnosis?

Little is known about the president’s physical condition, our newsroom’s resident doctor, the staff writer James Hamblin, reports.

“Based on age and sex alone, Trump is at high or very high risk for severe disease,” he writes. “Eight percent of COVID-19 patients ages 65 to 74 die from the disease. … But a key variable in Trump’s case is that, because he is president, he will have the best possible medical monitoring and care.” Continue reading James’s analysis.

Where is the president?

This afternoon, the White House announced that the president would spend the next few days at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, “out of an abundance of caution.”

The administration has maintained that Trump is continuing to work. However, our reporter David A. Graham notes that he’s been uncharacteristically quiet.

When did he get infected?

“It typically takes four or more days for the virus to multiply and reach detectable levels inside the body,” Alexis C. Madrigal and Robinson Meyer reported early this morning. They continue:

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that symptoms of COVID-19 are most likely to begin four to five days after exposure, but they have been observed to start anywhere from two to 14 days after exposure.

At the same time, current evidence suggests that people who have COVID-19 are most infectious at the very moment their symptoms begin.

Who else is sick?

First lady Melania Trump also tested positive, as did the Trump adviser Hope Hicks, Senator Mike Lee of Utah, and the University of Notre Dame president, John Jenkins.

“It would not be surprising if, in coming days, we learn that more members of Trump’s retinue and Cabinet have contracted the virus,” Alexis and Rob write.

Could Trump have infected Biden?

So far, the former vice president has tested negative, but experts warn that he won’t be totally in the clear for at least another week. Our staff writer Ed Yong analyzes the risks.

Did someone forward you this newsletter? Sign up here.

from The Atlantic https://ift.tt/2ETdL1U

Every weekday evening, our editors guide you through the biggest stories of the day, help you discover new ideas, and surprise you with moments of delight. Subscribe to get this delivered to your inbox.

In the years following Brown v. Board of Education, thousands of children desegregated America’s schools. “The task that fell to them was a brutal one,” our senior editor Rebecca J. Rosen writes.

White parents, and their children, attempted to block Black children from attending classes—often ruthlessly—using “bomb threats, beatings, protests. They physically blocked entrances to schools, vandalized lockers, threw rocks, taunted and jeered.”

In our new special project, titled “The Firsts,” our staff writer Adam Harris tells the stories of five students who lived through the transition.

Hugh Price

12 years old ♦ Taft Junior High School ♦ Washington, D.C., 1954

Price and his family fought for him to be one of the first Black students at his all-white high school in Washington, D.C. But once he was there, he “couldn’t wait for it to be over.”

Jo Ann Allen Boyce

14 years old ♦ Clinton High School ♦ Tennessee, 1956

Boyce and 11 other students desegregated their high school in Clinton, Tennessee. Then the riots came.

Sonnie Hereford IV

6 years old ♦ Fifth Avenue School ♦ Alabama, 1963

Hereford IV desegregated Alabama’s public schools in 1963. He was only 6 years old.

Millicent Brown

15 years old ♦ Rivers High School ♦ South Carolina, 1963

Brown changed Charleston, then watched it stay the same.

Frederick K. Brewington

9 years old ♦ Lindner Place Elementary School ♦ New York, 1966

Brewington’s education came at the end of a bitter civil-rights battle that engulfed New York State, more than a decade after Brown v. Board of Education.

33 days remain until the 2020 presidential election. Here’s today’s essential read:

The most illuminating moment of the debate occurred when the president went after one of Joe Biden’s children, Adam Serwer argues.

“Biden acted like a father, doing what almost any parent would have done,” he writes.

One question, answered: California continues to burn. Does wildfire smoke make COVID-19 worse?

The hosts of our Social Distance podcast talked with John Balmes, a pulmonologist who has studied inhaled pollutants for decades, to find out.

Here’s a snippet of their conversation:

John Balmes: One of the risk factors for smoke exposure is an increased risk of lower-respiratory-tract infections. That’s acute bronchitis and pneumonia, which is particularly problematic in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

James Hamblin: Does it increase your risk of having more severe disease once you’ve been infected if you’ve been living in a place that has high levels of exposure to particulate matter versus someplace else?

Balmes: Yes, there’s a building evidence with regard to air pollution, and particulate matter in particular, and COVID-19.

Find the full episode, “Fires Outside, Virus Inside,” on Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

Want to better understand this specific virus? Here are three key reads from our team:

We all need small delights. Here’s a break from the news:

This calls for a toast: Panic! at the Disco’s debut album, which turns 15 this week, is “an audacious and unlikely classic.”

Did someone forward you this newsletter? Sign up here.

from The Atlantic https://ift.tt/2GtG9rO

Every weekday evening, our editors guide you through the biggest stories of the day, help you discover new ideas, and surprise you with moments of delight. Subscribe to get this delivered to your inbox.

A COVID-19-vaccine rollout could be chaotic—and a true logistical nightmare, our health reporter Sarah Zhang warns in an essential new piece.

We caught up with Sarah to find out why—and hear the latest on the search for a vaccine.

The conversation that follows has been edited and condensed.

Caroline Mimbs Nyce: Why does this vaccine rollout have the potential to be such a headache?

Sarah Zhang: First, you have the challenge of getting what is very likely two doses of a vaccine to hundreds of millions of Americans in the middle of a pandemic. And they’re not interchangeable. If you get the first dose of one vaccine, you have to get that same vaccine as a second dose. So there’s gonna be a lot of paperwork involved.

Second has to do with the specific vaccines that are furthest along in clinical trials right now. They use new technology called mRNA, which hasn’t been used in vaccines before. The downside is that the technology is extremely fragile physically. One vaccine has to be kept at –94 degrees Fahrenheit, which you’re just not gonna find in a regular doctor’s office.

All these decisions have been made to get the vaccine out faster. But the trade-off is that they make them much harder to use in the field.

Caroline: You write in your piece that the first vaccine may not be the most important. Can you explain what you mean by that?

Sarah: Imagine: How are you going to get a vaccine that needs to be stored at –94 degrees into a developing country or a rural area? It seems pretty unlikely that that’s the vaccine that is going to be widely used across the world.

In the beginning, speed is really important. But as we hopefully develop more vaccines, how easy it is to use is going to be really important too.

Caroline: You’ve been cautioning readers to temper their expectations around a vaccine. What’s your advice going into this winter?

Sarah: Be patient. There’s a lot of cautious optimism that some of the vaccines that are in clinical trials are going to work.

It’s okay if some of them don’t; that’s the whole point of doing a trial. There will probably be news that feels disappointing, but that’s just a part of the process.

The fact that there are literally dozens of vaccines in the pipeline means that it’s very likely we’re gonna have one—or probably several—options. It’ll just take time, so we gotta hunker down, and wait for it.

What to read as you wait for tonight’s debate to begin:

Here are three things to think about.

1. Some Democratic operatives “see the debates as Biden’s best chance to blow an election,” our staff writer Edward-Issac Dovere reports.

2. Peter Wehner, a contributor to our Ideas section, thinks Biden should call out the president as “a terribly broken man.”

3. The responsibility to fact-check what the candidates say tonight lies with viewers themselves, argues John Dickerson, who moderated a 2016 Republican-primary debate.

Today’s break from the news:

Our happiness columnist shares his best tips for breaking through hopelessness. For starters: Change your definition of productivity.

Did someone forward you this newsletter? Sign up here.

from The Atlantic https://ift.tt/2Sae5wn

Every weekday evening, our editors guide you through the biggest stories of the day, help you discover new ideas, and surprise you with moments of delight. Subscribe to get this delivered to your inbox.

This election could be the one that breaks America, Barton Gellman warns in our November cover story. Given its magnitude, we published the piece early online; read it now.

Bart and I caught up over email to discuss the ways America’s election mechanisms might break down entirely.

The conversation that follows has been edited and condensed.

Caroline Mimbs Nyce: So what happens if President Trump refuses to concede the election?

Barton Gellman: I don’t think it’s a question of “if.” Unless Trump scores a legitimate win in the Electoral College, everything we know about him says he will refuse to accept defeat and use every tool at his disposal to undo the result.

Refusing to concede is a remarkably powerful thing. Concessions are how elections end, full stop.

Trump will have plenty of options to keep the outcome in doubt—in court, on the streets, in the Electoral College, and in Congress. The subtext of his efforts will be that “nobody knows” who won, and that he is stepping in to restore stability.

Caroline: You argue that the president could use his powers to muddle the results, leaving no clear procedural winner. How so?

Bart: Unlike baseball, elections have no umpire—no singular authority with the power to rule decisively on the results.

The most significant risk is that Trump will ask Republican allies in battleground states to appoint Trump electors regardless of the outcome. We’re accustomed to choosing electors by popular vote, but the Supreme Court has said a state legislature may take back that power from the people and name any electors it likes.

According to a legal adviser to Trump and three top Republican leaders in Pennsylvania, they are already discussing contingency plans to set aside the voting results—by claiming the vote count is rigged. Republicans control the House and Senate in all six of the most closely contested swing states.

Caroline: There are many frightening details in your piece. Is there one that keeps you up at night?

Bart: What frightens me is that Trump has the power, with only modest help from GOP elected officials, to throw the outcome into doubt and to keep it unresolved almost indefinitely. And if he throws the decision to Congress, which he can do almost at will, the law is a labyrinth full of dead ends when it comes to how that’s resolved. Experts tell me that the Electoral Count Act is so garbled and full of logic bombs that it can easily lead to deadlock.

If two men show up to be sworn in on January 20, the chaos candidate and the commander in chief will be the same man.

Caroline: What’s your best advice to Americans going into November?

Bart: First and foremost, stop thinking about this election in conventional terms. Expect an extraconstitutional challenge, because it is very probably coming.

Take agency, because an election can’t be stolen without some kind of acquiescence from the people at large. So don’t acquiesce.

Vote. Vote early if your state allows. Vote in person if you can tolerate the risk, because late-counted mail votes will be the heart of the postelection contest.

Have a question for Bart—or any of our political reporters—about the upcoming election? Tell us.

One question, answered: A reader named Sydney writes in from Toronto, Canada:

I heard an immunologist on the radio today say that a coronavirus vaccine could be only 50 percent effective, in which case we’d still have to “live” with the virus even after it arrives. With all the talk of the vaccine being the way out, this is terrifying. What if the vaccine isn’t totally effective?

James Hamblin responds in his latest “Paging Dr. Hamblin” column:

No vaccine is perfectly effective. That isn’t bad news; it’s just a basic fact. … But though vaccines are only partly effective at protecting a single person, they can still be extremely effective collectively.

Continue reading. Every Wednesday, James takes questions from readers about health-related curiosities, concerns, and obsessions. He’s also answered:

Have one? Email Jim at paging.dr.hamblin@theatlantic.com.

41 days remain until the 2020 presidential election. Here’s today’s essential read:

The president’s decision to proceed with a Supreme Court nominee “could spell trouble for swing-state Republican senators in tough reelection fights,” our White House correspondent Peter Nicholas reports.

What to read if … you need a break from the news:

Erin Brockovich, the film, turns 20 this year. Erin Brockovich, the activist, isn’t slowing down.

Did someone forward you this newsletter? Sign up here.

from The Atlantic https://ift.tt/3kMtSOj

The United States has never failed to clear the bar of electing its next president. For The Atlantic’s new cover story, Barton Gellman issues a devastating warning that––in this year of plague, recession, “a reckless incumbent, a deluge of mail-in ballots, a vandalized Postal Service, a resurgent effort to suppress votes”––the mechanisms of decision making are fragile and at meaningful risk of breaking down. In short, our democracy has never before experienced anything like this.

His report for The Atlantic’s November cover is “The Election That Could Break America.” The Atlantic is moving up its publication to today, weeks ahead of schedule, given the urgency of the reporting and the narrowing time until November 3. Merely by refusing to concede, which no other candidate has done in the modern era, Trump would have the tools to keep the outcome in dispute indefinitely. Gellman's reporting shows that Republicans are already discussing contingency plans to seize on this uncertainty to try to bypass the popular vote and directly appoint electors to the Electoral College.

“Begin by rejecting the temptation to think that this election will carry on as elections usually do,” Gellman writes. “Something far out of the norm is likely to happen. Probably more than one thing. Expecting otherwise will dull our reflexes. It will lull us into spurious hope that Trump is tractable to forces that constrain normal incumbents.”

Gellman reports that the worst-case scenario is not that Trump simply rejects the election outcome and refuses to leave. The worst case is that he could use his power to “prevent the formation of consensus about whether there is any outcome at all.” On January 20, 2021, “two men could show up to be sworn in. One of them would arrive with all the tools and power of the presidency already in hand.” This would be a genuine constitutional crisis. And as Gellman’s reporting shows, there is no umpire in this game, no singular authority that can tell the loser that he has lost.

Details from Gellman’s reporting that are of extreme consequence to the American public include:

Republicans are discussing contingency plans to bypass the popular vote and directly appoint loyal electors to the Electoral College. According to sources in the Republican Party at the state and national levels, Gellman reports that, using a “justification based on claims of rampant fraud, Trump would ask state legislatures to set aside the popular vote and exercise their power to choose a slate of Trump electors directly.” A Trump-campaign legal adviser tells Gellman that “the push to appoint electors would be framed in terms of protecting people’s will. Once committed to the position that the overtime vote has been rigged, the adviser said, state lawmakers will want to judge for themselves what the voters intended.” Three Republican leaders in Pennsylvania tell Gellman they had already discussed the direct appointment of electors among themselves, and one says he has discussed it with Trump’s national campaign.

The 2020 presidential election will be the first in 40 years to take place without a federal judge requiring the Republican National Committee to seek approval in advance for any “ballot security” operations. The consent decree, a court order forbidding Republican operatives from using any of a long list of voter-purging and intimidation techniques, expired in 2018 after a federal judge ruled that the decree had worked and Republicans hadn’t recently violated its terms. As a result, Gellman writes, “Republicans have launched a program to recruit 50,000 volunteers in 15 contested states” to monitor polling places and challenge voters they deem suspicious-looking.

If you are a voter, think about voting in person. In a year when the presidential election may be the first conducted primarily by mail, Trump’s continual decrying of mail-in voting as a fraud is not meant to prevent votes from being cast this way. His purpose is to discredit the practice, starve it of resources, and suppress votes. His attacks are funneling Republicans away from the mail-in ballots that he will suppress and attempt to disquality. Gellman writes: “Trump, in other words, has created a proxy to distinguish friend from foe. Republican lawyers around the country will find this useful when litigating the count. Playing by the numbers, they can treat ballots cast by mail as hostile, just as they do ballots cast in person by urban and college-town voters. Those are the ballots they will contest.”

With only weeks until Election Night, Gellman reports that right now, the best we can do is an ad hoc defense of democracy. “If you are a voter, think about voting in person after all,” he advises. “If you are at relatively low risk for COVID-19, volunteer to work at the polls. If you know people who are open to reason, spread the word that it is normal for the results to change after Election Night. If you manage news coverage, anticipate extraconstitutional measures and position reporters and crews to respond to them. If you are an election administrator, plan for contingencies you never had to imagine before. If you are a mayor, consider how to deploy your police to ward off interlopers with bad intent. If you are a law-enforcement officer, protect the freedom to vote. If you are a legislator, choose not to participate in chicanery. If you are a judge on the bench in a battleground state, refresh your acquaintance with electoral case law. If you have a place in the military chain of command, remember your duty to turn aside unlawful orders. If you are a civil servant, know that your country needs you more than ever to do the right thing when you’re asked to do otherwise.”

“Take agency. An election cannot be stolen unless the American people, at some level, acquiesce.”

“The Election That Could Break America” is published at The Atlantic today. The November issue will continue to publish online in the coming weeks.

from The Atlantic https://ift.tt/3cuKjfe